From Gucci Mane to JAY-Z, some of our favorite rappers have written memoirs. These are the best hip-hop autobiographies.

For an industry that has spun countless rags-to-riches tales over the past four decades, it’s hardly surprising that the rapper-penned memoir overshadows all other entries in the hall of fame for hip-hop books. Granted, this extensive library is filled with numerous classics that focus on everything but the artist—the majority of which document the genre as an art form (How to Rap: The Art and Science of the Hip-Hop MC) or the progression of hip-hop as a culture (Can’t Stop Won’t Stop: A History of the Hip-Hop Generation)—but none are quite as thrilling as the rap memoir.

Although you can learn a lot about an MC by listening to their records, autobiographies offer insights through a different lens: a long-form glimpse into the world of hip-hop seen through the eyes of its key players. These books are equal parts entertaining and inspirational. At their best, they function as both celebrity tell-alls and self-help therapy sessions.

Earlier this month, Common and Rick Ross became the latest rappers to join the hip-hop literary canon. Common’s second memoir, Let Love Have the Last Word, comes out on May 7. Ross’s first book, Hurricanes (co-written by Neil Martinez-Belkin, who also co-authored The Autobiography of Gucci Mane) is set to arrive on September 3. In preparation for these forthcoming must-reads, let’s take a look at the most fascinating hip-hop memoirs to date.

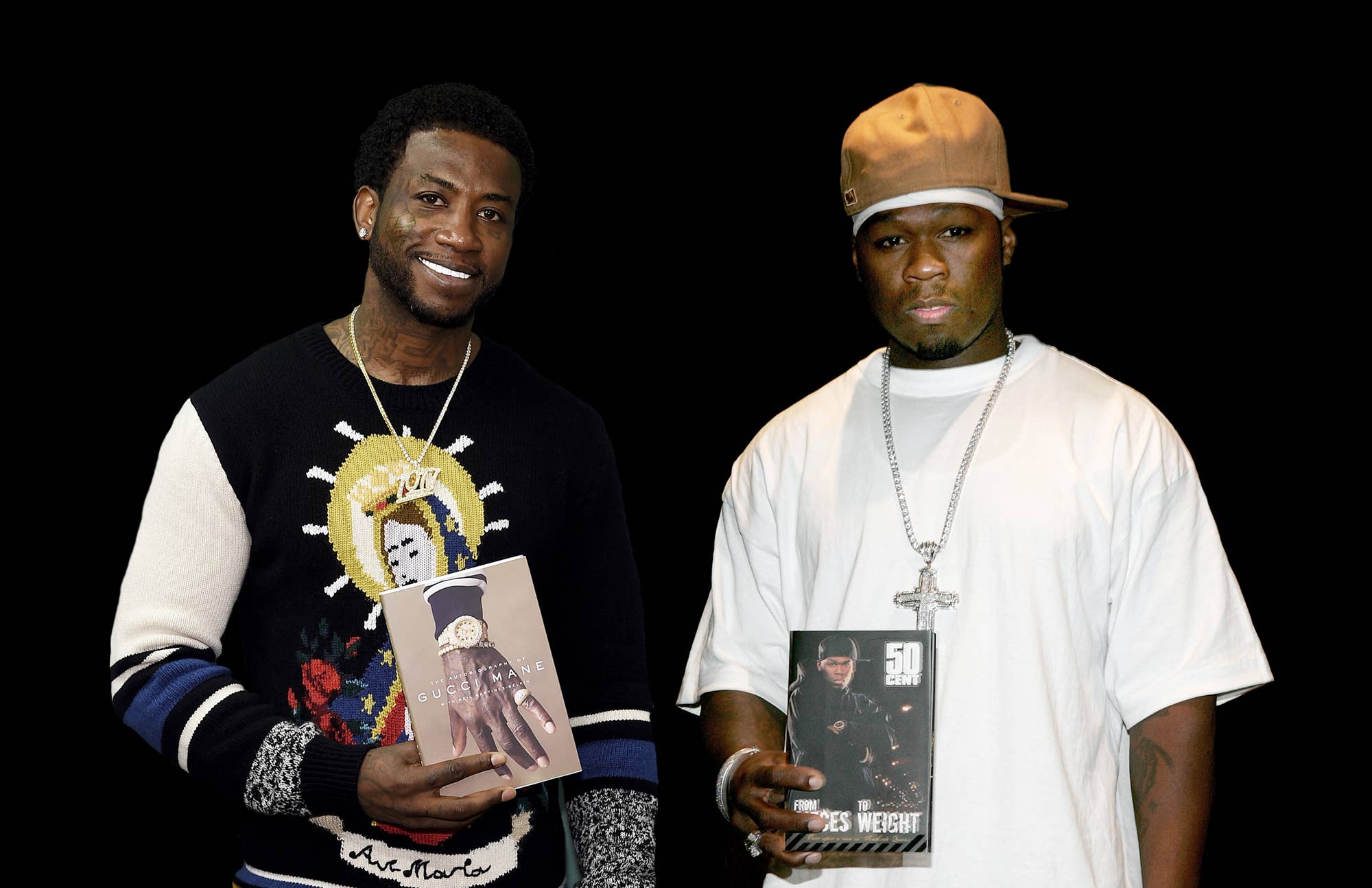

Gucci Mane, ‘The Autobiography of Gucci Mane’

Publisher: Simon & Schuster (2017)

One of the most recent entries into the hip-hop literary canon, The Autobiography of Gucci Mane is worthy of being mentioned amongst the best memoirs ever penned by an MC. While Gucci’s story has been well-documented since his meteoric rise in the late-’00s, his position as one of the most influential figures to enter the rap echelon in the past decade, makes this book a must-read for hip-hop fans.

Unlike most superstars in his era, Gucci’s story is a slow-burn, a narrative that the memoir chronicles in full. The book follows Gucci’s career from his early buzz in Atlanta to his dominating run on the mixtape circuit, on through his explosion into the mainstream, subsequent incarceration, and post-prison comeback in recent years. This latest chapter in Gucci’s career is his victory lap, a period in which he’s re-solidified his status as the godfather of Atlanta’s trap sound, while charting the course for hip-hop’s next generation of SoundCloud rappers-turned-superstars.

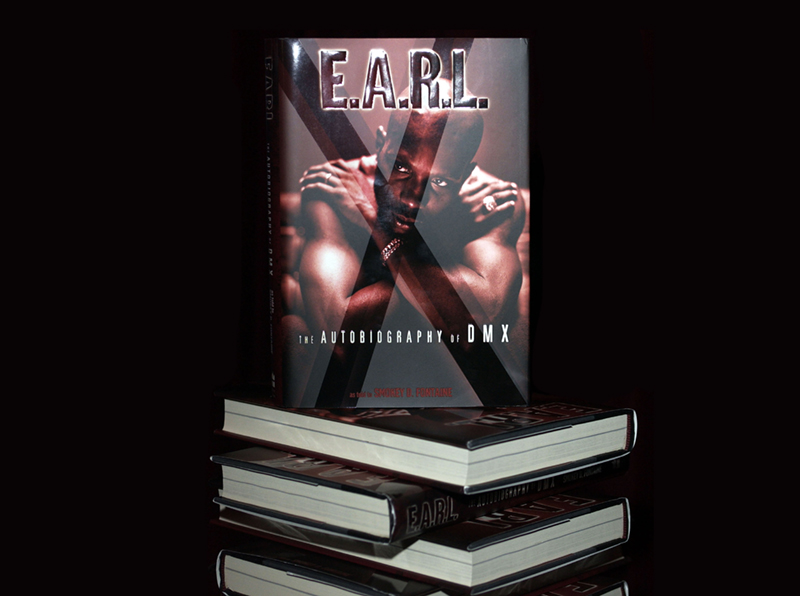

DMX, ‘E.A.R.L.: The Autobiography of DMX’

Publisher: It Books (2002)

Unlike most hip-hop memoirs, The Autobiography of DMX was released when its protagonist was still operating at the peak of his powers. DMX was only three weeks removed from becoming the only artist in the history of the Billboard 200 chart to reach No. 1 with his first five albums: a record that lasted 13 years, until Beyonce scored her sixth straight No. 1 with 2016’s Lemonade. For an MC as raw and uncut as X, it felt like his story had already been told, delivered over nearly 100 tracks spread across his five solo albums.

On the other hand, a rags-to-riches story as mesmerizing as DMX’s never grows stale, which is a point the book drives home by offering up new insights on X’s tough past. The autobiography outlines particularly violent robberies he administered as a youth, and the brutal beatings he experienced at the hands of his mother and her boyfriends. More than anything, though, the book functions as a painfully honest account of Earl Simmons’ journey from poverty-stricken youth to rap superstar. It also serves as a reminder of a timeless adage: The sky’s the limit.

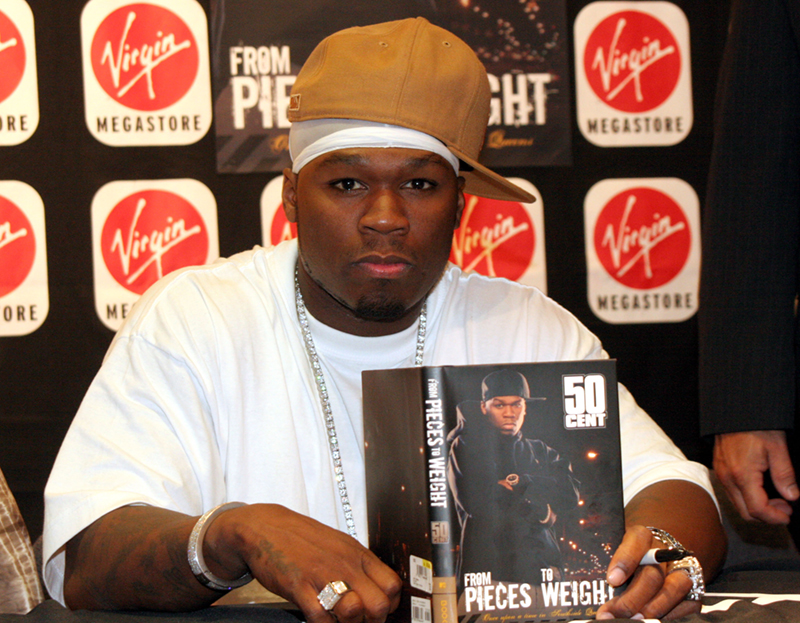

50 Cent, ‘From Pieces to Weight: Once Upon a Time in Southside Queens’

Publisher: MTV Books (2005)

50 Cent’s come-up was mythical: After getting shot nine times outside of his grandmother’s home, he was dropped from Columbia and blacklisted from the industry. He recorded song after song after song in a Queens basement and got hot on the mixtape circuit. One tape landed in the hands of the biggest rapper alive, Eminem, who invited him to come to Los Angeles and meet Dr. Dre. After signing a million-dollar record deal, he scored the biggest opening-week hip-hop debut of all time with his first proper studio album, 2003’s Get Rich or Die Tryin’.

By 2006, 50’s haunting life story and subsequent rise to superstardom had been well documented. Over the preceding three years, it transcended hip-hop and grabbed ahold of Hollywood, inspiring the 2005 biopic, Get Rich or Die Tryin’. As a result, when From Pieces to Weight: Once Upon a Time in Southside Queens arrived one year later, it was initially met with confusion: What kind of entertainer writes a book after telling their story on film? Of course, running out of stories has never been a concern for 50, which he (along with writer Kris Ex) proved in his autobiography. Introspective and violent, From Pieces to Weight drips with street wisdom and raw insight, and spins the tale of Curtis Jackson into something bigger: a re-telling of the American dream.

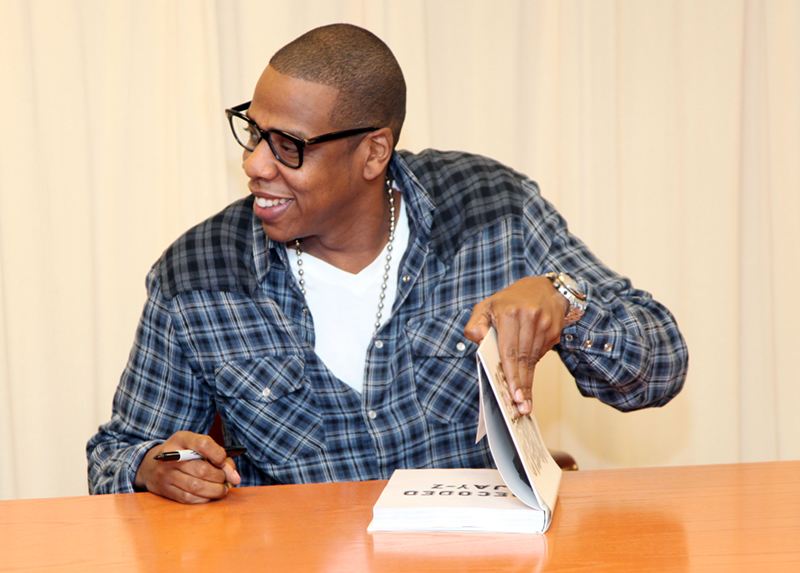

JAY-Z, ‘Decoded’

Publisher: Spiegel & Grau, Penguin Random House (2010)

“Everywhere I went, I’d write,” Jay-Z recalls early on in Decoded. “If I was crossing a street with my friends and a rhyme came to me, I’d break out my binder, spread it on a mailbox or lamppost and write the rhyme before I crossed the street.” Thus began his love of words, an affair that would mold him into one of the best lyricists hip-hop has ever seen, and one of the greatest songwriters of our time.

The most rewarding parts of Decoded, though, take place when Jay turns his attention to his own lyrics, submitting a lyrical analysis that celebrates the complex wordplay he’s recognized for. Though it shouldn’t come as a surprise, the GOAT’s ability to deliver one of the greatest rap memoirs of all-time is nothing short of spectacular.

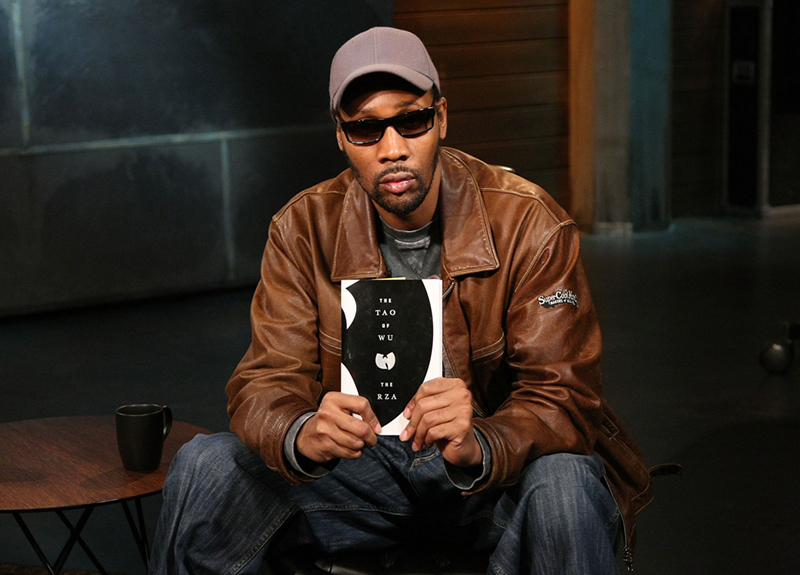

RZA, ‘The Tao of Wu’

Publisher: Riverhead Books (2009)

The Tao of Wu is exactly what you’d expect from a book written by the mastermind behind the Wu-Tang Clan. Part memoir, part spiritual guide, RZA’s follow-up to his 2005 bestseller The Wu-Tang Manual is a masterstroke in the hip-hop literary canon.

For Wu-Tang stans, the book is filled with juicy stories of the group’s early days (including the time RZA saved Method Man’s life at the scene of a drug deal gone bad on Staten Island) but also focuses on their unprecedented camaraderie, a bond formed and strengthened by watching kung-fu movies and marathon recording sessions. At its core, though, The Tao of Wu digs deeper, as RZA submits a spiritual message that embraces 5 Percent Nation Muslim teachings as well as Zen Buddhism. Sure, it’s long on mythology and, at times, is a little bit preachy, but, as with all things Wu-Tang, I wouldn’t want it any other way.

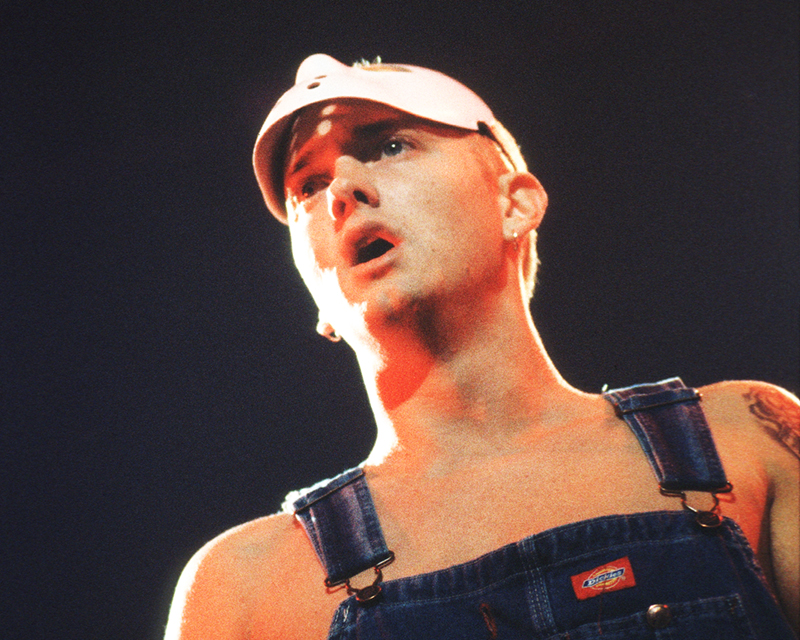

Eminem, ‘The Way I Am’

Publisher: Dutton (2008)

Near the end of 2004, at the height of his fame, Eminem disappeared. At the time, he was five years into his prime, a remarkable run that saw him cement his status as the top-selling artist in hip-hop history on the strength of four consecutive multi-platinum No. 1 albums (2000’s The Marshall Mathers LP, 2002’s The Eminem Show and 8 Mile Soundtrack, 2004’s Encore).

Following the release of Encore that November, Eminem became a recluse. He spent the next few years in hiding, struggling with the death of his best friend, Proof, whose 2006 murder sent Eminem into a downward spiral, culminating in an addiction to prescription pills that landed him in rehab. Nearly four years into his self-imposed absence, he returned to the rap game, not with music but a memoir, The Way I Am, which hit stores in October 2008.

Part autobiography, part photo gallery, the book gave Em a chance to speak with his fans, on the record, while not on record. While his familiar story is crisper in 8 Mile, and his delivery as a writer pales in comparison to his skill as an MC, The Way I Am is essential for other reasons. It was one of the first times he shared his private life with the world, as the misunderstood rapper shed light on his struggles with fame, addiction, depression, and the death of Proof.

DJ Khaled, ‘The Keys’

Publisher: Crown Archetype (2016)

After a monster 2016, which saw DJ Khaled transform into a pop culture force on the strength of his Snapchat account, he capped off the biggest year of his career with his first book, The Keys. Doubling down on the motivational wisdom he spews on social media, Khaled came correct with a self-help book that feels authentic thanks to his undeniable self-belief. Even if, at times, his familiar schtick is drilled into the reader’s brain to the point of exhaustion.

Built around his personal philosophy for success, The Keys sees Khaled share his major keys, from “Be honest but don’t play yourself” to “Don’t drive your Jet Ski in the dark,” along with breaking down his popular catchphrases, such as “another one,” “secure the bag,” “special cloth alert,” and “bless up.” While it’s easy to scoff at his various aphorisms, it’s just as effortless to simply follow his step-by-step instructions. Three years removed from his apex, it feels like we could use some of Khaled’s exuberance in 2019.

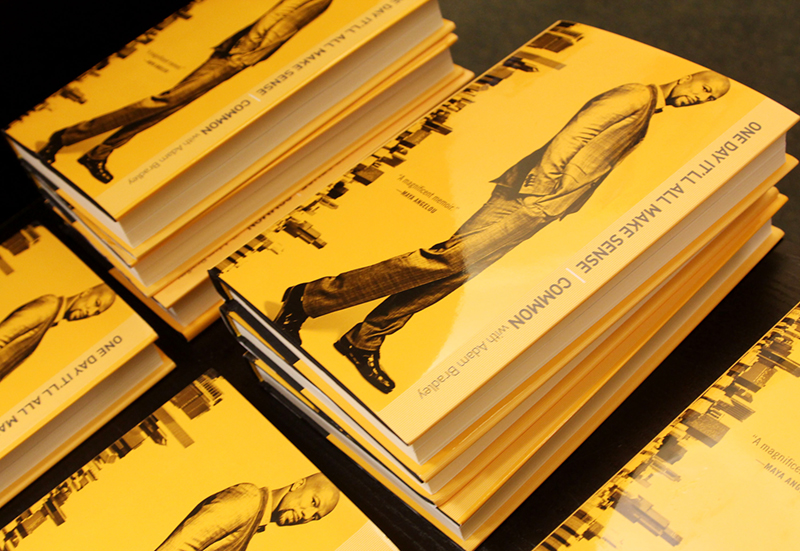

Common, ‘One Day It’ll All Make Sense’

Publisher: Atria Books (2011)

One Day It’ll All Make Sense hit shelves on September 13, 2011, two months before Common would send stray shots at Drake on “Sweet” (the third single from the former’s 2011 album, The Dreamer/The Believer) and four months before Drake would respond by chastising the Chicago rapper from going from God to broad, on his guest verse on Rick Ross’ “Stay Schemin.”

Now, I don’t bring this up as a point of reference; rather, One Day It’ll All Make Sense sheds light on the mindset Common was in right before he decided to initiate an unwinnable beef with the hottest rapper alive. Though the book is inspiring, funny, and gripping—highlighted by never-before-told stories about his encounters with hip-hop legends like Tupac, Biggie, Ice Cube, and Lauryn Hill, as well as political icons such as Barack Obama and Nelson Mandela—at times, it contradicts everything Common built his career on. Celebrated as a conscious rapper who embraces themes of love and faith, the book finds him question those labels, all while detailing his experiences running with a gang (which finds him practically boasting about beatdowns- and degrading women). And yet, you’re rooting for him the whole time, largely because of his world-class charisma, which jumps off the page to pull you back in. If you don’t believe me, you clearly haven’t read Common’s writing while listening to Be on repeat.

Prodigy, ‘My Infamous Life: The Autobiography of Mobb Deep’s Prodigy’

Image via Getty/Des Willie

Publisher: Touchstone (2011)

It’s fair to argue that My Infamous Life: The Autobiography of Mobb Deep’s Prodigy is not the best rap autobiography of all-time; but what you can’t argue with is this: no hip-hop memoir is quite this impressive, considering that it was written (with the assistance of journalist Laura Checkoway) while Prodigy was incarcerated for three years on a gun charge. However, this is not to say that the circumstances surrounding its creation make My Infamous Life appear better than the actual story told between the covers. Context aside, it would still be one of the best memoirs in hip-hop history.

While the book gives an intimate look at P’s background—his battles with drugs, his struggles with sickle-cell anemia, his life of crime—My Infamous Life shines brightest when it functions as an ode to New York City’s hip-hop scene, specifically the period that’s recognized as the Mecca’s apex: the early-to-mid-’90s, a stretch that coincided with the simultaneous peaks of Nas, The Notorious B.I.G., Wu-Tang Clan, and Mobb Deep. This is where Prodigy, who’s never been one to shy away from beef, chronicles legendary rap feuds like the East Coast–West Coast rivalry, as well as his beefs with Jay-Z, Nas, Snoop Dogg, Ja Rule, and Capone-N-Noreaga. For true hip-hop heads, it contains some of the most compelling stories ever published by a rapper.

Lil Wayne, ‘Gone Til November: A Journal of Rikers’

Image via Getty/Jason LaVeris

Publisher: Plume Books (2016)

On March 10, 2010, Lil Wayne began serving an eight-month stint at New York’s notorious Rikers Island Correctional Facility, on weapons chargers. By the time he got out that November, the hip-hop pecking order had changed: Young Money upstarts Drake and Nicki Minaj had each encroached on Wayne as the hottest rappers on the label. Of course, it wasn’t until his first post-prison offering (2011’s Tha Carter IV) failed to live up to expectations, that fans started to mull over the possibility that Rikers had changed Wayne.

Hip-hop heads began to speculate on how the rapper’s incarceration ended his prime. Six years after his release, it looked like we were about to get our answer via Gone ‘Til November, a published version of the journal Wayne kept while on Rikers, which arrived in October 2016. Unfortunately, the memoir is nothing like prison life as it’s portrayed in movies. In other words, it’s boring, and details ho-him stresses like encountering mice, gaining weight, and dealing with your cellmates’ bodily functions, among other trivial events. Still, for those of us old enough to remember when Lil Wayne was running circles around the rap game, the memoir is must-read material, if only because it’ll make you consider one of the most overlooked what-ifs in recent hip-hop history: If Wayne doesn’t go to jail, how many more years of Apex Weezy F Baby do we witness?

Scarface, ‘Diary of a Madman: The Geto Boys, Life, Death, and the Roots of Southern Rap’

Image via Getty/Santiago Felipe

Publisher: Dey Street Books (2015)

Scarface is often overlooked when we discuss the best rappers of the ‘90s, with legends like Nas, Biggie, 2Pac, Jay-Z, Snoop, and André 3000 soaking up most of the praise. Not only is Scarface worthy of being mentioned alongside hip-hop’s greats, he’s equally as influential; one of the first true rap icons from the South, he was a pioneer who shed the stigma surrounding Southern rappers. In turn, he paved the way for regional hip-hop hotbeds like Houston, New Orleans, and Atlanta.

Scarface’s lasting legacy—particularly when looking back at his contributions to hip-hop in light of today’s climate—is that he serves as the touchstone for emo rap’s mass appeal. While fellow rappers were often focused on violence, Scarface’s music dealt with grim subjects like death and depression. In that same breath, Diary of a Madman picks up right where his catalog left off, moving with the same morbid rhythm that backed many songs in his discography. After reading about his suicide attempt and two-year stay at a mental health facility as a teen, you have no choice but to hear “Mind Playin Tricks on Me” in a bleaker light.

Questlove, ‘Mo’ Meta Blues: The World According to Questlove’

Image via Getty/Nicholas Hunt

Publisher: Grand Central Publishing (2013)

In some ways, Amir “Questlove” Thompson is the last rap artist you’d expect to write a memoir. An abashed hip-hop aficionado, you’d think he respects the genre too much, not to mention he’s the polar opposite of the prototypical hip-hop alpha-dog (self-deprecating, unselfish, and honorable). At the same time, this makes him the perfect figure in the rap game to pen an autobiography. What other hip-hop star doubles as both a critic and journalist, let alone genuinely loves the art form more than Questlove? No one.

As such, it’s hardly surprising that Mo’ Meta Blues (the title is a nod toward Spike Lee’s 1990 joint) is incredible, largely because Quest is a true music geek. Throughout the book, Q is at his most excited when discussing music, rather than career accomplishments. He’s a damn good storyteller, too, as evidenced by his tales of run-ins with Prince and KISS, among others. But his greatest skill is his ability to resonate as a fan—so convincingly that it’s easy to forget you’re reading an autobiography written by Grammy-winning artist.

Ja Rule, ‘Unruly: The Highs and Lows of Becoming a Man’

Image via Getty/Rob Verhorst

Publisher: Amistad (2014)

Naturally, I was disappointed to find out that Unruly was more focused on Jeffrey Atkins, the reflective father and loyal husband, than his alias, Ja Rule, the superstar rapper. Does this make me selfish? Hardly. If anything, I merely want Ja to be recognized for what he once was: one of the best pop crossover artists in all of hip-hop. Sure, even at his absolute apex, he may have slotted behind Jay-Z, Eminem, and Nas, when it came to the “Best Rapper Alive” rankings, but on the radio and pop charts, Ja was once the biggest commercial force in the rap game.

Consider his two-year run between October 2000 and October 2002: Ja released back-to-back No. 1 albums, 2000’s Rule 3:36 (3x platinum) and 2001’s Pain Is Love (3x platinum), along with 2002’s The Last Temptation, which peaked at No. 4 on the Billboard 200 and was certified platinum. Even more impressive, he notched three No. 1 singles (“Always On Time,” “I’m Real,” “Ain’t It Funny”), and four others that peaked inside the top 10 of Billboard’s Hot 100 (“Mesmerize,” “Livin It Up,” “Put It On Me,” “Between Me And You”).

Long before Fyre Festival tainted his reputation, and even before 50 Cent destroyed his career, Ja Rule was hip-hop’s biggest hit-maker. What does this have to do with Unruly: The Highs and Lows of Becoming a Man? Everything. If he hadn’t suffered one of the worst fall-offs in rap history, we wouldn’t be waxing poetic about a book that merely reminds us of what he used to be.